Carbon Accounting

Carbon accounting is messy, but we have to get it right

Carbon accounting – the process of detailing and auditing a company’s emissions – is a relatively simple concept to explain. The need to understand how much pollution a firm produces is growing both environmentally, as a way to understand where mitigation is most possible, and legally due to increasing regulation around disclosure. Isaac Hanson, Thematic Reporter explains.

Unfortunately, putting it into practice is significantly more complex. There are currently at least eight major standards and frameworks in use globally, each with their own requirements, calculations and outputs. Some larger companies produce reports in-house, but, as with traditional accounting, many firms use external auditors.

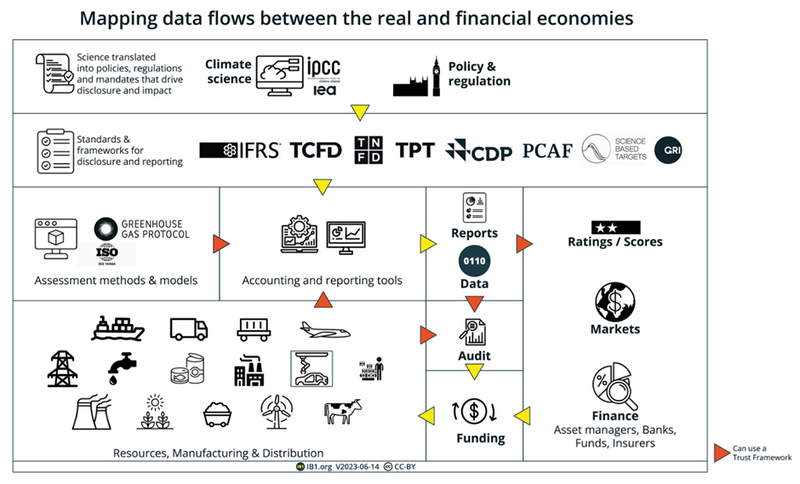

Credit: IB1

Icebreaker One (IB1), a UK non-profit that aims to bring businesses, governments and regulators together to harmonise carbon reporting, provides a simplified infographic on its website followed by a breakdown of the basic principles in the ecosystem. Even this runs to over 1,000 words, but it avoids the complex details of actually doing an audit in practice.

Open carbon?

Founder Gavin Starks was also the founding CEO of the Open Data Institute (ODI) and a key developer of Open Banking standards, two other non-profits in the UK that aim to use big data to automate and simplify complex tasks.

His time at the ODI was an important influence on the way he set up IB1. Starks tells Energy Monitor, a stable publication of GlobalData: “We convene multiple stakeholders across industry and government to collaborate on the rules they want to apply, then help them implement it … We’re not creating new standards, we’re not creating a carbon calculator. We’re helping the data flow in a way that uses those things and creates cohesion around how people can do this in the same way.”

The firm is also notable in its focus on small and medium enterprises (SMEs) as opposed to the multinational corporations that tend to be involved in carbon accounting. Project Perseus, headed up by IB1 and Bankers for Net Zero, is an initiative targeted at SMEs in the UK with the aim of enabling simpler carbon accounting. It does this by collecting electricity usage data from smart meters, providing an interoperable baseline from which companies can be judged. The goal, Starks said, is “to do one thing well.”

Gavin Starks, Founding CEO, Open Data Institute (ODI)

Standardisation challenges

Even this posed challenges. Data from smart meters is legally and logistically difficult to access, with many of the 150 UK energy retailers using different systems to record their outputs. Starks explained that Perseus is working with the retail energy code to alter code so that they can even use electricity data for environmental means.

Within the UK, various push factors are making interoperable carbon accounting standards essential.

Starks explains: “You've got mandatory reporting coming downstream, regulated through the financial economy … You've got a whole acronym soup of different things, which people are broadly confused by and a bit terrified of. It is not a solidified landscape; it's moving. So that introduces its own risk.”

“That's forcing organisations to ask [for emissions data] downstream into the SME community and obviously the SME community is sitting there going, A, we don't understand this, B, we don't have any time and C, we don't have any money. We want to get on board with a Race to Zero. But please, could you help us? And so, when you look at these different forcing functions, you've got a perfect storm of chaos in the middle of that.”

Big companies are frustrated by this lack of interoperability too. One task that the non-profit has been commissioned to perform is an audit of all the available carbon accounting solutions currently in the UK. Its current running total is 160. This means that even those which can afford to hire external auditors are unlikely to be operating on the same metrics – or producing comparable results.

Accuracy is key

Philippe Pernstich, Founding Footprinting Lead at carbon accounting firm Minimum, is among those who want to change this. He tells Energy Monitor: “The legacy model, and where I came from previously … is consultants using Excel, basically, to footprint.”

In the past, this kind of model has been sufficient, but as government regulation and public pressure rise, so too does the need to truly understand how much greenhouse gas emissions companies are producing.

Minimum, in contrast, offers a full carbon accounting solution examining scope one, two and three emissions. Pernstich emphasises that the quality of data and methodologies is as important as the quantity of data. Scope three emissions – indirect emissions produced upstream and downstream in the supply chain – are often calculated through spend-base accounting, which uses US Energy Information Administration (EIA) data to calculate emissions based on the expenditure of a company.

“It gives you a sense of where your big emissions lie, but in terms of monitoring and tracking progress over time, that isn’t going to help you in any way because the only way you’re going to reduce that footprint is by spending less,” Pernstich explains. “This is not necessarily the lever that you’re going to pull to reduce emissions.”

Moving away from EIA data is essential in the long run, but the problems in calculating scope three emissions go back to what Icebreaker One is trying to solve, “Suppliers are getting a dozen different questionnaires from a dozen different customers asking the same things in a slightly different way.”

Philippe Pernstich, Founding Footprinting Lead, Minimum

How H&T’s attestation process works with Chainlink for stablecoins to ensure not too many are minted. Credit: Harris & Trotter”

What can be done?

To that end, Minimum has joined The Carbon Call, an initiative funded by Microsoft’s philanthropic organisation and climate philanthropy organisation ClimateWorks. The project aims to accelerate the creation and diffusion of best-practice carbon accounting standards. IB1 is also a member, and founders include Microsoft, GSK and KMPG.

Despite the organisation’s strong corporate backing, it is still yet another organisation attempting to standardise carbon accounting. There is a certain irony in the proliferation of standardisation organisations, though Carbon Call describes itself as “complementary to existing pledges [such as CDP or the Race to Zero]”.

Phillipe acknowledges this dichotomy: “We’re seeing this proliferation of voluntary, mandatory and regulatory reporting requirements. I think that now we are just about seeing the beginnings of a bit of consolidation at the same time, and the beginnings of some attempts for consolidation with ISSB and carbon call, [with] all these dictionaries that look at translating the requirements from European reporting requirements [such as the CSRD] to the IFRS reporting requirements, etc.”

We may be in the “wild west phase of carbon accounting”, but time is running out to find a way out of it. UN General Secretary António Guterres warned last month that “humanity has opened the gates of hell” in response to the proliferation of extreme weather events over the past year. He also encouraged wealthy countries to hit net zero by 2040, a target that is far from likely under current conditions.

If Earth is to survive the century, carbon accounting needs more clarity more quickly.

Main image: