Restructuring

Restructuring plans to protect supply chain

In times of distress to the supply chain, boards may need to consider restructuring and looking to alternative options to protect their businesses and themselves, advises Amy Jacks, Partner, Restructuring, Mayer Brown International LLP

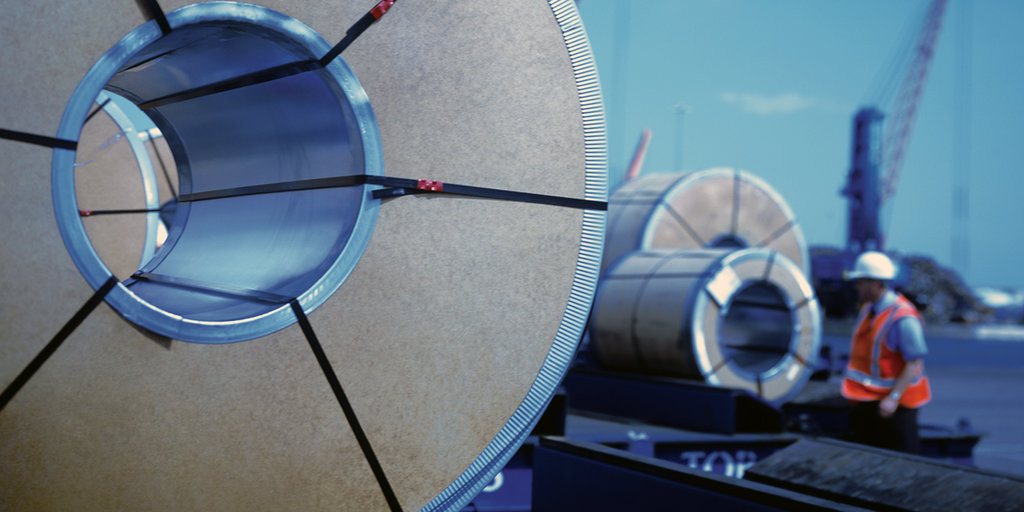

The recent decision by the UK government to extend the existing tariffs on steel imported from certain countries such as China by a further two years is part of a wider debate around globalisation versus nationalism. Whilst views on protectionism as opposed to free trade will differ, it is clear that the Covid-19 pandemic has highlighted the fragilities of global supply chains and led to businesses considering how best to protect themselves against dislocation or supply chain failure.

Amy Jacks

Partner, Restructuring

Mayer Brown International LLP

In the UK, Brexit has an effect on trade with our European neighbours and the war in Ukraine has exacerbated an already fragile supply chain with global shortages of key commodities, substantial increases in raw material and freight costs which, alongside spiralling energy prices, are causing substantial problems to businesses who are unable to pass those inflationary costs on to their customers. Companies are also focussed on ESG issues and so it is not surprising that many are considering whether to de-globalise and looking to ‘near-shore’ their supply chain.

Active management of supply chain issues has never been more important as these headwinds gather force. Key contracts should be audited to ensure that you are clear on your rights: time is often of the essence in an insolvency scenario, so should a key counterparty fail, a clear chain of command within the business and an understanding of your rights can make the difference between a successful or unsuccessful outcome. Companies should have a methodology in place for monitoring key counterparties for warning signs, such as late or non-payment; attempts to renegotiate terms; decline in quality of goods or services; unexpected or recurring changes in management; late filing or qualification of accounts; court judgments and rumours. Where possible, consideration should also be given to a counterparty's wider group, as failure in one part of the group could pull the rest down where for example cross-guarantees have been given by all group companies to a lender. To the extent that there are fundamental challenges within the supply chain, or if companies find that they are unable to pass through the increased costs that have been inflicted upon them, there are a variety of restructuring options available to them.

In addition to the well-known processes such as administration, liquidation or CVA (company voluntary arrangement), legislation in June 2020 (which was expedited by the Covid-19 pandemic), introduced new tools for struggling businesses, such as the standalone moratorium and the Restructuring Plan.

The moratorium leaves management in charge but with a licensed insolvency practitioner acting as Monitor. The moratorium is for an initial period of 20 days (which can be extended), and provides companies with a holiday from certain debt payments. In this window of time, there is a prohibition on enforcement action such as forfeiture by landlords or bringing legal proceedings. To enter into a moratorium, there are two conditions: (i) the directors must be able to state that the company is or is likely to become unable to pay its debts; and (ii) the monitor must agree that the moratorium will likely result in the rescue of the company as a going concern. The moratorium may therefore be a useful tool for a business that simply needs some ‘breathing space’ to bridge to a certain point, for example to facilitate a transaction or to finalise a restructuring of the business.

A Restructuring Plan can be used by companies facing (or likely to encounter) financial difficulty, to reach a compromise with creditors – importantly including secured creditors (unlike a CVA which can only bind unsecured creditors). The Restructuring Plan also introduced a new “cross class cram down” concept into English law i.e. the ability to bind a dissenting class of creditors, where (i) the court is satisfied that none of the dissenting class would be any worse off under the Restructuring Plan than they would in the ‘relevant alternative’ (i.e. the alternative scenario that would most likely occur if the Restructuring Plan were not sanctioned) and (ii) at least one class with a genuine economic interest in the company has voted in favour. This cross-class cram down construct is a really important development as it means that, where a company cannot negotiate a consensual restructuring with its stakeholders, it can now use the Restructuring Plan to effect a restructuring of the company, even if there is dissent, that addresses all classes of creditor and should allow for ongoing viability.

In summary, active management of supply chain to mitigate problems should they arise and a proactive approach to one’s own business in this incredibly difficult economic environment is imperative. The tools are available should boards act early when faced with financial difficulty.